Carlos Amato, Leslie McCanne, Chengyuan Yang, Daniel Ostler, Osman Ratib, Dirk Wilhelm & Lukas Bernhard https://rdcu.be/cYHOw

Abstract

Purpose

Today’s hospitals are designed as collections of individual departments, with limited communication and collaboration between medical sub-specialties. Patients are constantly being moved between different places, which is detrimental for patient experience, overall efficiency and capacity. Instead, we argue that care should be brought to the patient, not vice versa, and thus propose a novel hospital architecture concept that we refer to as Patient Hub. It envisions a truly patient-centered, department-less facility, in which all critical functions occur in the same building and on the same floor.

Methods

To demonstrate the feasibility and benefits of our concept, we selected an exemplary patient scenario and used 3D software to simulate resulting workflows for both the Patient Hub and a traditional hospital based on a generic hospital template by Kaiser-Permanente.

Results

According to our workflow simulations, the Patient Hub model effectively eliminates waiting and transfer times, drastically simplifies wayfinding, reduces overall traveling distances by 54%, reduces elevator runs by 78% and improves access to quality views from 67 to 100% for patient rooms, from 0 to 100% for exam rooms and from 0 to 38% for corridors. In addition, the interaction of related medical fields is improved while maintaining the quality of care and the relationship between patients and caregivers.

Conclusion

With the Patient Hub concept, we aim at rethinking traditional hospital layouts. We were able to demonstrate, alas on a proof-of-concept basis, that it is indeed feasible to place the patient at the very center of operations, while increasing overall efficiency and capacity at the same time and maintaining the quality of care.

Purpose

Current healthcare systems around the world are characterized by the organizational principles of segmentation and separation of medical specialties. They are structured into departments and facilities which offer the best service in their respective field but are not properly coordinated or tightly linked to the rest of the healthcare ecosystem. Consequently, today’s hospitals seem more a collection of different “departments” and medical fields than a fully integrated cooperative and service-oriented facility. Each department uses its own workflow schemes or standard operative procedures (SOP), employs specially trained personnel, and runs its medical service in well-circumscribed and precisely defined structures and areas. Communication between disciplines is often limited to the absolute minimum necessary for coordination tasks, e.g., regarding forwarding of relevant patient information and time scheduling of examinations or interventions.

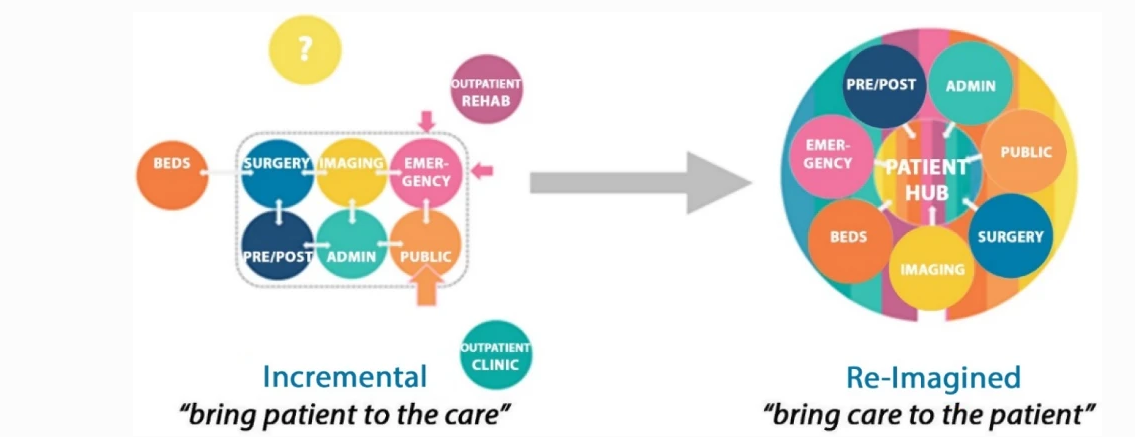

The current system requires patients to step from doctor to doctor and from department to department to collect the jigsaw puzzle pieces of their disease. It is a serious drawback of current hospital structures that patients often need to tell their medical history and symptoms over and over again to the medical staff of different disciplines and subspecialties. The request and scheduling of different diagnostic examinations across departments are often confined to a very succinct standard requisition, neglecting the exchange of any additional patient-specific information (e.g., the anatomical reconstruction after gastric surgery in case of a postoperative CT scan to rule out complications). This data that are essential for appropriate programming and interpretation of diagnostic procedures is often non-accessible to the physician performing the exams. We call this “incremental care” and in this traditional model, the patient is constantly moved around to receive care (Fig. 1 depicts an exemplary traditional patient’s pathway). While some of these issues could be addressed by optimizing the clinical communication and data storage infrastructure, we believe that by means of architectural choices it becomes possible to further benefit and simplify the necessary workflows and to reduce the amount of required technology.

Current hospitals are organized around well-separated specialized clinics and expert units, which all by themselves are perfectly tuned for economically optimized and efficient use of their dedicated infrastructure (e.g., the operating room in surgery or the MRI in radiology) and make efforts to reduce the cost of personnel wherever possible. Profit has become the main driver of healthcare and everything else including patient satisfaction and even quality of care often comes as a second priority. However, financial profit is generally not assessed on a global scale of patient management services but rather on the level of subsystems and specialized services, with a focus on separated profit centers which results in higher global costs rather than reducing them due to inefficient coordination and consolidation of clinical pathways. “Service-oriented” care units refer more to medical services (or equipment) and teams providing dedicated care, rather than to patient-centered care facilities. This often results in inefficient workflows such as excessive and unnecessary time spent in waiting rooms, which is becoming prevalent in large facilities.

Although system optimization works well for a specialized and restricted field, e.g., a department or a single facility, the entire healthcare system has grown enormously toward becoming rigid, not-adaptive, and slow. It is not designed for the active prevention of disease, but for mere reaction in case an adverse health event or development arises. This approach entails that the patient suffers more overall, since diseases are allowed to develop and manifest themselves before they are finally diagnosed and treatment can be started. At the same time, the burden for clinical care facilities increases as well, since treatments become more complex and result in longer durations of stay. The preventive approach has been advocated for quite some time now and its benefits have become very obvious during the recent Covid-19 pandemic

Although “interdisciplinary care” and “overarching approach” represent typical buzzwords of modern treatment concepts, the integration of involved clinical disciplines remains on a low level. One notable exception is acute trauma or emergency management where any active action is focused on the patient and collaboration is crucial to handling critically vital situations. The growing field of emergency medicine could serve as a model for a more global paradigm shift, as an example of healthcare delivery that is, above all, patient-centered. In such a context, interdisciplinary communication is highly standardized involving all persons and services required for well-protocoled patient management scenarios. Services are brought to the patient, and not vice versa, and anything and everybody involved is geared to facilitate a fast and comprehensive treatment. It has been shown that the patient-centered multidisciplinary approach, at least for acute trauma, can save lives and is superior to traditional concepts . So, one might ask whether such an approach could also be beneficial for other indications or even for general care? And if so, will this new concept maintain the current standard of care and the relationship between caregivers and patients?

As a central building block for addressing the issues described in the previous we present our new hospital concept that we refer to as Patient Hub. It envisions a truly patient-centered, department-less facility, where all the critical functions occur on one floor. While our idea is not intended to solve all of today’s hospital design flaws (and we are fully aware that one solution will never fit all models), we aim at providing concepts and tools to help re-think traditional designs.

Methods

We developed a novel, one-of-a-kind design concept for the hospital of the future. The envisioned facility is fully patient-centered and strives for a workflow-oriented design by clustering related functionalities and processes in defined hubs, all located on the same floor and in close proximity to each other. In order to demonstrate the effectiveness and added value of our proposed hospital architecture, we benchmarked this new concept against a traditional design. For that, we reconstructed both the Patient Hub and an exemplary traditional hospital layout using 3D simulation software and compared them with regard to workflow efficiency and patient satisfaction. For the initial analysis presented here, we chose a typical patient scenario based on a common real-world case.

The patient hub concept

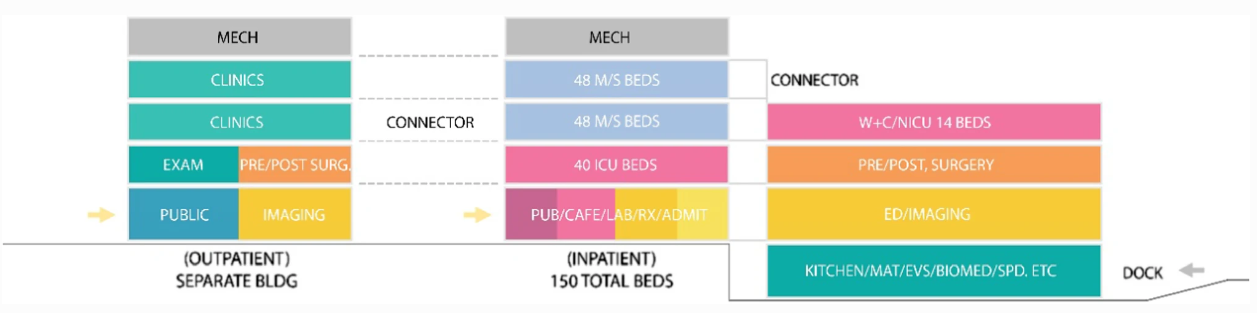

Today’s hospital buildings are often fancier versions of the 1960s bed-tower-on-diagnostic-and-treatment podium model, with a lot of newer technology crammed inside. In accordance with the principle of decentralization, which is prevalent in many healthcare systems around the world , such environments are characterized by being divided into departments and individual silos, each possessing its own organizational structure (including permanent staff, assigned space and beds), optimized for operational and financial efficiency. The patient is moved around from place to place to receive care, instead of bringing the care and technology to the patient (e.g., infrastructure like CT or MRI is often inconveniently and remotely located in a different building, as illustrated by Fig. 2).

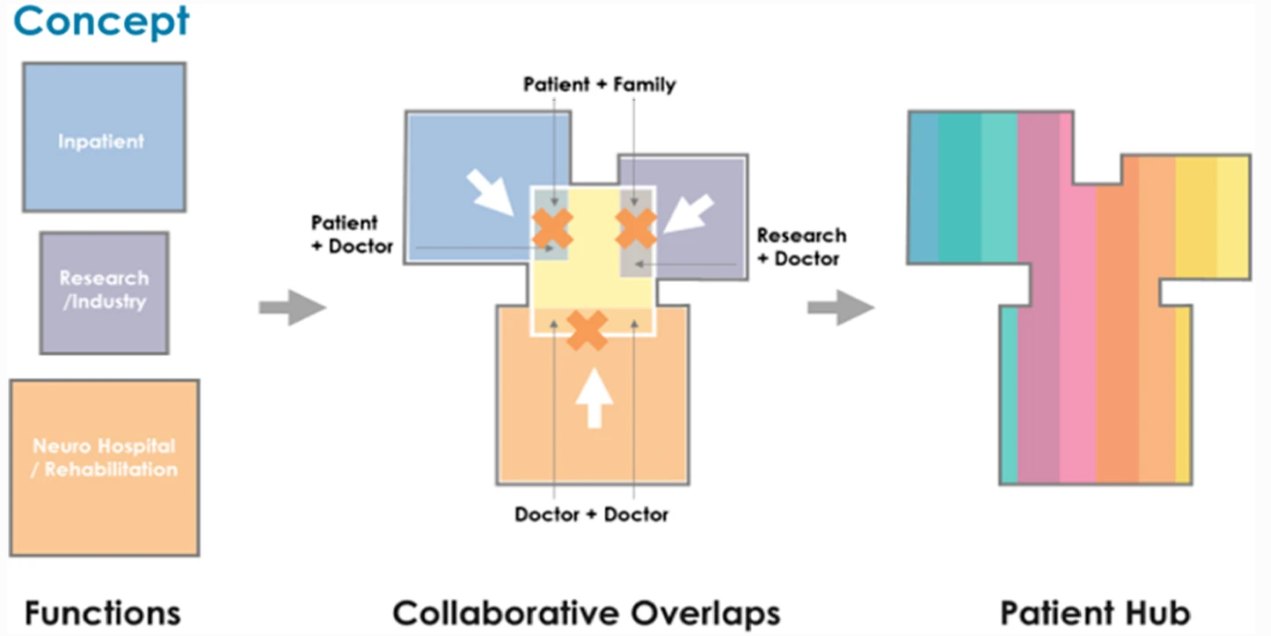

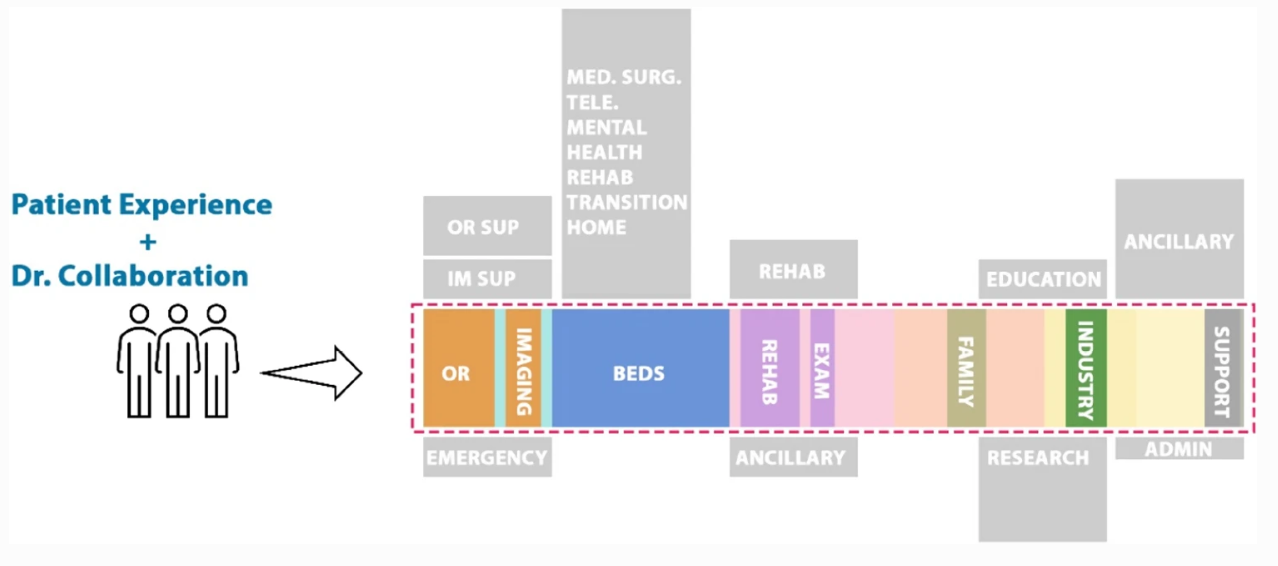

In contrast, our Patient Hub concept is a radical departure from the way traditional hospitals are designed. It envisions a transformative “one of a kind” and truly patient-centered, department-less facility. We propose a highly centralized clinical layout, where all relevant medical fields of expertise are available within the same space surrounding the patient (see Figs. 3 and 4). They form clusters which contain functionalities of equal classes, as for example examination, out-patient care or administration. For the patient, the whole system has a single-entry point to simplify wayfinding and is designed to minimize patient movement. The centralized clinical layout brings together staff from all specialties to encourage clinical collaboration and care coordination, thereby stimulating health care performance [5]. Instead of facilities being distributed along the hospital, and most often on different levels or even buildings, the new design concept aims at achieving a logical and self-explaining layout by bringing together what belongs together. However, the vision of the Patient Hub encompasses much more than a traditional hospital: This new environment (or ecosystem) co-locates outpatient, inpatient, rehabilitation, wellness and prevention, ancillary support spaces, and industry (research and development) all under one roof. It is envisioned to be no longer just a site for the treatment of the sick but a health-oriented all-encompassing facility, which is achieved by implementing patient-centered structures and workflows as well as by an expansion of services to also incorporate prevention and wellness.

Instead of being department-oriented, the Patient Hub design follows a more functional approach. To avoid getting lost in the sub-channels of the system (different departments with specific ecosystems), the architecture is logically constructed and patient-centered. It features a single point of entry, and a central meet and commute “core” to which the relevant facilities (housing, examination, out-patient care, administration) are linked, just as the arms of a tree are joined to the trunk. For the reduction or even full avoidance of patient moves, the respective areas cluster the required functionalities on one site. This will be done irrespective of the affiliated department or responsibility. Instead of passing from the radiologic department in level A to cardiology in level D to complete the pre-operative check-up, the patent will now move from one to the other door, as depicted in Fig. 5.

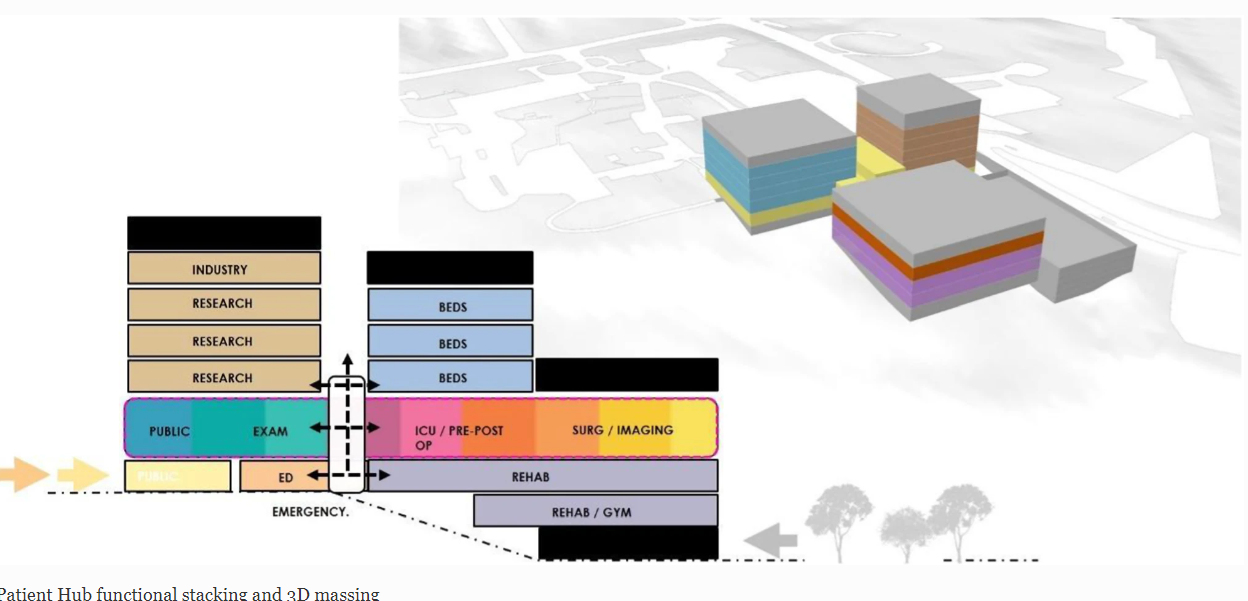

By avoiding duplicating functionalities which today are replicated in every department (e.g., waiting rooms, registration area, observation area) the Patient-hub concept aims at saving space, simplifying patient pathways, and facilitating implementation and adaptation of new treatment concepts. While keeping this functional patient-hub design with all required functionalities being logically distributed on one floor, we envision different levels of the building to be adaptable to different patient needs and specialties, like surgery, medical treatment, rehabilitation, etc. (see Fig. 6).

Due to its horizontal layout and resulting space demands, the Patient Hub layout in its most essential form is best suited for freestanding greenfield hospitals. The hub floor of our current design requires an 8,000–9,000 square meter floor plate but can be scaled up and down depending on the number of beds and procedure space needed. Since a further increase of the horizontal expansion would start to contradict the goal of having a compact centralized hub with streamlined workflows and short routes, we instead propose to stack multiple independent Patient Hub units vertically. Thereby, it becomes possible to retain the compact size of each hub and keep all movements of a given patient on the same floor, while making more efficient use of the available building ground and increasing the overall capacity.

Patient scenario

Our exemplary scenario revolves around a patient being diagnosed for rectal cancer. First, the patient receives general examination and diagnostics according to current guidelines [6], which include endoscopy, pelvic MRI and CT. After physical examination, which, due to his age and existing comorbidities includes cardiologic assessment, the case is discussed in multidisciplinary consultations such as tumor conferences and the patient is scheduled for surgery. Preparation measures for surgery include obtaining the patient’s informed consent by the surgeon and anesthesia, as well as preoperative preparation such as bowel cleansing and blood tests. After the intervention, observation in the ICU is carried out for one day, before the patient is returned to the regular ward. In our scenario, an eventless postoperative course is observed, which is why only a chest x-ray is performed to examine the postoperative lung status. No other tests or assessment of anastomotic healing are undertaken. During the hospitalization, the patient has an interview with the surgeon, to discuss upon the results of surgery and eventually additional treatments, and another interview with the social worker to decide upon auxiliary measures. Finally, the patient is discharged from the clinic.

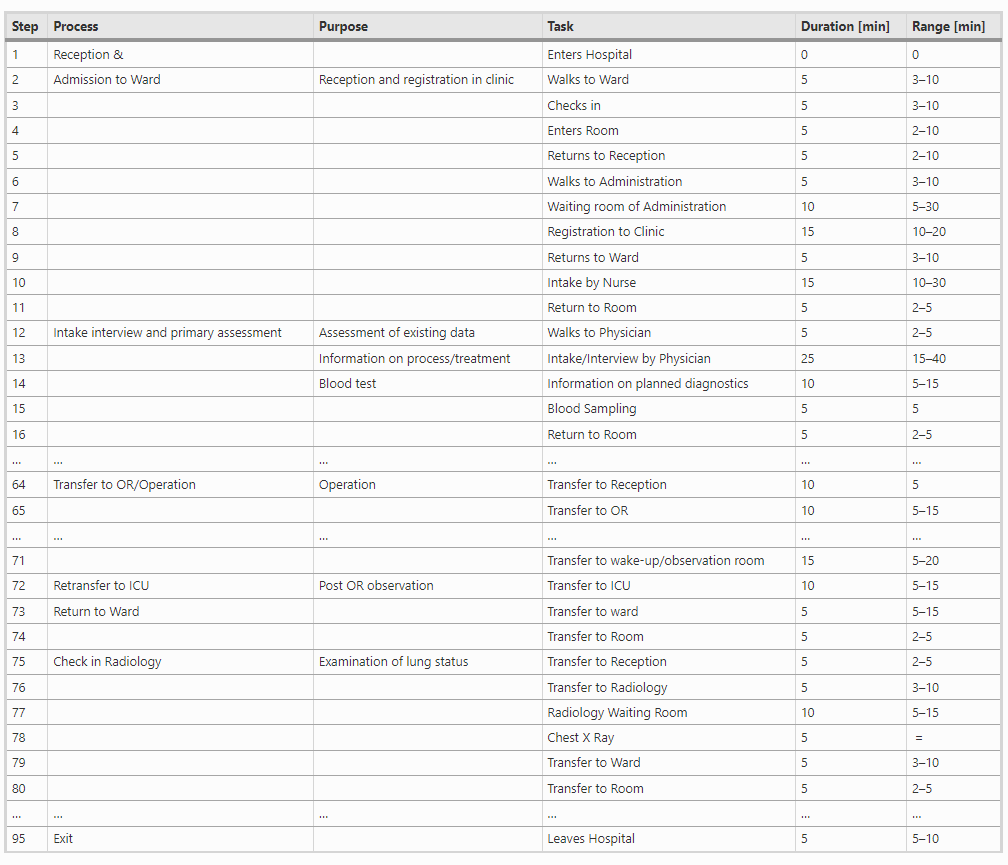

The case above describes a common situation that clinicians are dealing with regularly and is based on the organizational structure and standard operating procedures of a university hospital. We analyzed the necessary steps along this clinical pathway for a traditionally designed hospital. Even though we chose a complication-free course for our scenario, the resulting list of necessary steps contains 95 entries, many of which are describing a change of the patient’s location or time spent within various waiting rooms. Refer to Table 1 for an excerpt of this list.

Workflow simulation

Using the 3D simulation software FlexSim Healthcare™ (FlexSim Software Products, Inc., Orem, Utah, USA), we developed dynamic models for comparing various quality measures between our two different hospital layouts. FlexSim Healthcare is a standalone healthcare simulation product aiming to model patient flows and other healthcare processes. It is designed to help healthcare organizations to evaluate different scenarios and validate them before they are implemented. For that, one or several architectural models can be created, followed by the definition of patient journeys. During execution of the simulation, FlexSim can monitor data contributing to patient satisfaction, including the total time spent, time spent for each treatment, time proportion of receiving care, travel distances, etc. It can also be used to analyze staff and equipment utilization rates and help to balance staff workload and amount of equipment.

Modelling of architectural layout

We selected Kaiser Anaheim hospital, a traditional hospital with a similar size, to be compared to the Patient Hub. The construction of this hospital was based on a generic “template” hospital plan developed and used by Kaiser-Permanente, the US largest non-profit Health Management Organization (HMO) (Fig. 7). This plan was developed when the organization was required to replace half of its hospital beds in California due to new seismic regulations and resulted in a prototypical hospital “template” that can be built on virtually any site, with few modifications , with a minimum of effort, lead time, and government review . The design aimed at incorporating the best known clinical practices and design success stories and was optimized for a fast and efficient construction process . Due to these characteristics, and a broad and successful implementation, we have selected this layout as the best comparison available today.

Full Article: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11548-021-02540-9#citeas